Keystone Cops in Uttarakhand

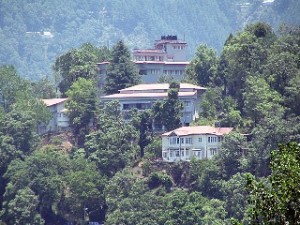

This story is 20 years old as I find myself writing it in 2008 — presently, I have finished working in Thailand and am on holiday in Laos before returning to Chengdu in China where I’ve previously worked. The story’s message has a deeper meaning for me now as I have shared some of my life with illegal refugees (as I once found myself to be one of them). At the time this story began, I was a younger man and had just completed my B.A. in south India while living in a small village near Madurai, Tamil Nadu. Another student from my college had invited me to visit him in Mussoorie, U.P. Mussoorie is a hill town in the Himalayan foothills where many British colonialists used to retreat to during the hot summer months from the baking plains of Uttar Pradesh. As such, it is a charming place to visit and live. I wasn’t there long before my friend recommended that I visit the ashram of a friend of his. It was located in the hills at about 8,000 feet elevation near the local district seat of Tehri Garhwal. This little town will loom large in my story. The town is now a part of the new Indian state of Uttarakhand that was carved out of the existing state of Uttar Pradesh — but that is another story and one that I’m not going to get into now.

Although I had finished my B.A. in south India, I was living as an illegal alien having overstayed my original tourist visa but with the tacit permission of the Tamil state government. I had received a piece of ‘legalese’ paper that said I could stay while my request for an extension of my tourist visa was funneled up the ‘Indian bureaucratic ladder’ where it was eventually rejected. It was a strategem that had enabled me to stay in Tamil Nadu for an extra year in which time I had finally graduated from Friends World College, that has since become the Global College program at Long Island University in New York. In 1988, on my own in the Himalaya, I only possessed a photocopy of my passport and a little money saved in the bank. I used this same strategem to live as an illegal alien for many years in Nepal — yet another story. Perhaps, this explains some of my affinity with and support for the plight of illegal refugees living all over the world.

Having finished my B.A., I had applied for and gained admission to another college in the U.S.A. I had no choice but to apply for another student loan to sustain myself alone and living in India. I had no funds to leave India or return to the U.S.A. I correctly — but at a future price — figured that I could visit this ashram in the Himalayan foothills and reside there until my independent M.A. study plans would be approved and my post-graduate studies could begin. At the ashram, I ‘earned my keep’ by taking care of the ashram’s cows. I learned to graze them and helped prepare their feed. It was my first — but, not last — experience of life in a cow shed. In the evenings, I would work on the details of my M.A. study plan and help prepare dinner. There were a few kids — orphans — and a retired, gentle British man to keep me company and help make things interesting.

By the time I had been there for six months, I felt at home in my new abode in the hills. Little did I know my holiday was over. The swami at the ashram informed me one morning that the local immigration police had requested him to bring me into their station to check out my papers and visa. I could have just left the hills and traveled back to south India but I still wanted to start my studies. I decided to ‘just go with the flow’ and see what would happen. It was a strange journey since the police at the station didn’t know what to do with me when I could only show them a photocopy of my passport.

What I was unaware of at the time was that a major construction project of a large dam was about to get underway back in that little town of Tehri Garhwal. The dam construction was being supervised by Russian engineers and any foreigners staying in the area were ‘suspect’. Complicating this scenario was the fact that the leader of an ‘anti-dam movement’ in the town was a close friend of the swami whose ashram I was visiting. As the dam was to be built over a fault line, the local resistance to its construction was understandable. There is a history of earthquakes triggered by dams, including several caused by the construction of the Hoover dam in the U.S.A. Scientists have recently theorized that the earthquake in Sichuan Province in May, 2008 may have been triggered by recent dam construction there. I am teaching near there, in Chengdu, again in 2009 and hope to research this to satisfy my curiosity. Meanwhile, back in Tehri Garhwal, I had really stepped into some ‘deep shit’! The police finally decided to take me to the local jail in Tehri Gahrwal — it is the ‘holding center’ for cases in that district. Now, another complication raised its ugly head — the local judge was on holiday. No one knew what to do with me.

What I was unaware of at the time was that a major construction project of a large dam was about to get underway back in that little town of Tehri Garhwal. The dam construction was being supervised by Russian engineers and any foreigners staying in the area were ‘suspect’. Complicating this scenario was the fact that the leader of an ‘anti-dam movement’ in the town was a close friend of the swami whose ashram I was visiting. As the dam was to be built over a fault line, the local resistance to its construction was understandable. There is a history of earthquakes triggered by dams, including several caused by the construction of the Hoover dam in the U.S.A. Scientists have recently theorized that the earthquake in Sichuan Province in May, 2008 may have been triggered by recent dam construction there. I am teaching near there, in Chengdu, again in 2009 and hope to research this to satisfy my curiosity. Meanwhile, back in Tehri Garhwal, I had really stepped into some ‘deep shit’! The police finally decided to take me to the local jail in Tehri Gahrwal — it is the ‘holding center’ for cases in that district. Now, another complication raised its ugly head — the local judge was on holiday. No one knew what to do with me.

Finally, the local authorities decided to take me to New Delhi and let another judge decide what to do with this crazy, cow-herding foreigner. Enter the Indian ‘Keystone Cops’. In a scene straight out of one of those old comedies of errors piled one on the other, the two policemen assigned to escort me on the train to New Delhi had also never had this kind of duty to perform before. No one had informed them of how to pay for our meals, snacks or drinks on the train. So, even though I was in ‘hand-cuffs’ for the whole journey and had to endure the curious stares of other travelers, it was up to me to feed us all from my own pocket money. Nevertheless, we finally arrived in New Delhi and traipsed to the court where the judge decided to just send us back to Tehri Garhwal. He had decided that only THAT district’s judge could address my case. Off we were, yet again on the train, for the hills.

By this time, I had already been in custody for about a week or so. My stay at the jail ended up being 7 weeks long, or exactly 49 days. I now find myself planning on spending another 49 days in Laos — not in jail — but completing a fast before continuing a self-assigned pilgrimmage to North Asia. Look for that story to begin in 2010 either in Mongolia or Siberia. Seven is supposedly a lucky number — what is 7 squared? I don’t know except that it is a long time to stay in a jail where you cook your own meals, have your ankles chained together at night, and sleep under an old army blanket on a cement slab for a bed. The judge finally returned from his vacation to find this sick foreigner in his jail’s clinic. I was suffering from amoebic dysentery — did I forget to mention this additional complication? However, the worst was over. A letter had arrived from my college’s local center’s director and his name was well-known and respected by the judge. The American consul had also showed up to assure the local authorities that I wasn’t a ‘spy’ but just an unofficial and rather naive student trying to manage things on his own. Local newspapers had written about me — asserting that I had a hidden, secret radio transmitter somehow hidden in the base of my antique, Royal portable typewriter. “What next?” I wondered at the time.

Well, on the day of my release from the jail, my swami’s friend, the anti-dam movement’s leader met me and handed over my student loan check for $7,500. It had arrived in the mail and was better than any ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card that I could have lucked into drawing in that other game of chance (Monopoly). The dice had finally been rolled in my favor. I was able to leave the country within ten days as ordered by the court, my amoebic dysentery had been treated, my lice-infested clothes had been exchanged for new ones bought in New Delhi, and I went home for the first time in a number of years. After visiting my family for a month and getting a new passport, I returned to India and often revisited the hills where I had first been so unlucky. Only, now, I stayed in other, safer ashrams and enjoyed my studies. The swami who took me to jail that day in the hills was murdered by one of his own staff. I even met the murderer while in jail. He was an Indian soldier with a medical discharge for schizophrenia. At the time we met, I could appreciate what he may have been experiencing. If there is a lesson or moral anywhere in this story, maybe it’s that life is full of surprises and we should expect — even prepare — for them if we are able.

One might also conclude that it’s important to choose one’s teachers carefully — especially if you’re going to trust them with your life. The teacher who supported me at the time with his sponsorship and hospitality was also there for me when I lost my own father — soon after that last visit home. The ‘hard’ lessons were really ‘flowing’ back then. I went on to Nepal and helped another family that had also lost its father — applying my share of life insurance funds from my father’s estate — to helping that family recover. The lesson here is called “Service to Others” as opposed to “Service to Self”. I believe and know in my heart it is the “ONE” lesson we have to learn here on Earth. We all must make that freewill choice for STO in order to grow and evolve into an awareness of the spiritual beings that we ARE. I can only hope that this story may inspire you to at least consider that a divine reality DOES exist even if we don’t have access to it as often as we may desire.

Filed under: India and

Leave a Reply